In any language, words both evolve and are created out of thin air. It is not unusual for a certain person or place to become associated with a trend, item, or invention and for that name to then become a common word in a language. These words are called 'eponyms' and the English language has several examples. Here are four:

Why not start with the most delicious of the eponyms? The Earl of Sandwich was an avid cardplayer (ahem, gambler), and he wouldn't leave the table for his meals. Instead, he would eat a piece of meat served between two slices of bread, an easy meal to hold in one's hands without a lot of extra silverware cluttering up the playing table. As the story goes, his fellow cardsharks came to so closely associate this meal with the Earl they started asking for a 'sandwich.'

A much less appetizing word than sandwich, 'gerrymander' is the process of apportioning legislative districts in such a way as to be politically beneficial to one party or another. The name results from legislation signed by Massachussetts Governor Elbridge Gerry that resulted in a salamander-shaped district in the Bay State. Combine Gerry + Salamander and you get both a compound word and an eponym!

It just sounds cool, right? Like the name just makes sense? The instrument's name didn't just appear out of thin air, though! It's named for its inventor, Adolphe Sax. We can just assume he was pretty hip.

Rudolf Diesel gives his name to this form of gasoline and engine. He invented the diesel engine in the early nineteenth century, and while he might not be widely remembered his name is widely used to this day.

If you dig further, you'll find plenty of other examples of eponyms in the English language. If you're interested in finding more, we recommend looking in the science sector, as inventions and discoveries lend themselves well to eponyms.

17 April 2017 | english quirks |

The English language is beautiful, complex, and sometimes unwieldy. Even with its nuance and vast selection of words, however, the English language has gaps where other languages don't. Sometimes the human condition and our complicated world just need a word that English doesn't have. Here are four words from other languages that we either need to adopt or establish our own version of:

What a novel idea - a word for a situation that nearly everyone has found themselves in!Tartle is that point in time where you forget someone's name, but you're supposed to be saying the name, most often in introduction. In English, we just call it awkward, but "tartle" has a much nicer ring to it, don't you think?

Ever been tired and had bags under your eyes? You're human, of course you have. But in France, you wouldn't need to use four words to describe the unsightly look of a night without sleep. The French simply call those dark circles "cernes."

Have a pile of books you've owned forever, keep adding to, but have never read? If you live in Japan, you'd be committing tsundoku, a very useful Japanese word for the book hoarders in the world.

April Fools Day must be wild in Indonesia. They have formal words for classic tricks! Mencolek is the Indonesia word for what in English we are forced to call "the lame prank where you tap someone on the wrong shoulder but are really on the other side so they look and don't see anything but immediately know what happened because that is literally the oldest trick in the book." Mencolek is much more efficient to say, don't you think?

English, for all your charm, you can make things just a little too complicated sometimes. These four words are only a few of the probably hundreds, if not thousands, of examples of words foreign languages simply do better than English.

20 March 2017 | words english needs |

The English language can be very strange indeed. In fact, it's so strange that there are many words which have two meanings (at least) and those meanings are the opposite of each other. How's that for confusing? This phenomenon is so common in English that it even has two words to describe it - auto-antonyms and contronyms. Here are four common contronyms that you've probably used:

1. Cleave

You can either "cleave to" something, or cleave something off. Think of a cleaver - a giant knife you use to cut something apart. If you come across a person discussing cleaving you, pay attention to the preposition they are using - they're either a stalker or a serial killer. Or, for all you optimists, maybe they're perfectly nice and just have an odd way of speaking.

2. Dust

When you dust the furniture you are removing the dirt and grime from it, right? But what if you're a baker and you're dusting a cake with powdered sugar? You're not taking it off, you're putting on a dust-like substance (albeit a much tastier one). Children's book character Amelia Bedelia was once famously thrown off by this contronym when she literally threw dust onto her employer's furniture.

3. Garnish

If you've ever had your wages garnished, you know its not a good thing. Your wages are certainly not being added to, rather money is being taken away from you. To the contrary, if you are garnishing a dish you are adding pretty features to it, perhaps a jaunty kale leaf or an orange peel. However, if your spouse has a dish that looks better than yours you might be excused for garnishing a chunk of that lobster from their plate...

4. Clip

A barber clips your hair, in fact he has a tool named after this action (clippers, naturally). In this sense, clip means to remove hair from you. You can also clip coupons to remove them from the newspaper inserts. But, because English is complicated, you can clip papers to hold them together. You can clip your hair back to make it stay in place, and you can clip a cellphone to your belt to look super cool.

English is strange, and it can be complicated. But it never ceases to be fun to explore - even if you have to pay special attention to context and prepositions to make sure words don't literally mean the opposite of their intended use.

6 March 2017 | english quirks |

Whether you are a native English-speaker or you learned it as an additional language, you'll have had plenty of moments where you just could not think of the right word. Maybe you ended up replacing it. Maybe you used a longer phrase instead. If you speak another language, perhaps the problem was not that you could not think of the right word, but that there is no English equivalent for it at all!

Here are a few of our favorite words from other languages that do not have an English translation, but that we think English should absorb as soon as possible!

Kummerspeck (German)

The German word kummerspeck translates literally as "grief bacon". It is the excessive weight gain suffered while emotional eating, particularly emotional eating to avoid negative feelings, such as after a breakup or because of stress.

Gattara (Italian)

The closest thing in English to the Italian gattara would be a "crazy cat lady". A gattara is an elderly lady who devotes her time to caring for stray cats. While our “crazy cat lady” generally takes in the stray cats, caring for them in her own home, a gattara feeds and cares for homeless cats on the streets.

L’ésprit d’escalier (French)

If you have ever walked away from an argument or discussion only to think of a great comeback a few minutes or hours later, the French have a word for that, l’ésprit d’escalier. The word translates as "staircase wit" and came about because philosopher Denis Diderot said he would think of a great response only by walking away and literally walking down the stairs.

Sobremesa (Spanish)

There must be a word for when people are done eating but they continue having a great conversation, right? Not in English, but the Spanish word is sobremesa.

Those are a few of our favorites, but how about yours? What do you feel the urge to express, but aren't able to because the word just isn't there?

28 February 2017 | words english needs |

Consider the following sentence:

he moped around the house, upset because he had crashed his moped

See the problem? The words "moped" are one example of the kinds of words we usually refer to with colorful language only repeatable after the watershed. They are homographs - words which are spelled the same but pronounced differently. There is a subset of homographs which are not just pronounced differently, but actually have a different number of syllables depending on which meaning you are going for.

Along with file and file, learned and learned, tier and tier and a few dozen others, these represent just one problem with counting syllables with a computer.

21 February 2017 | english quirks |

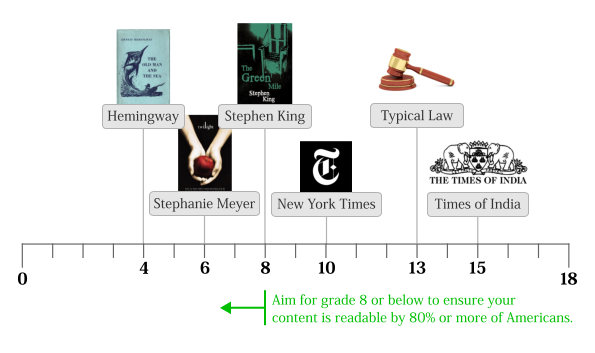

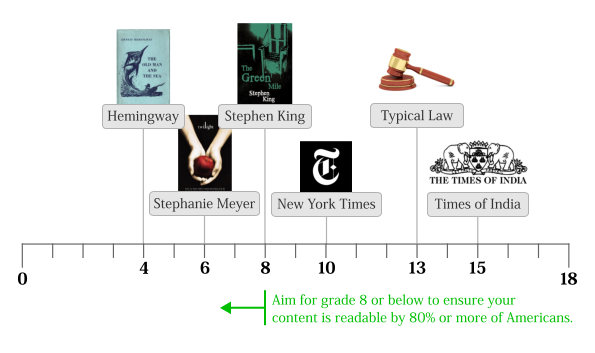

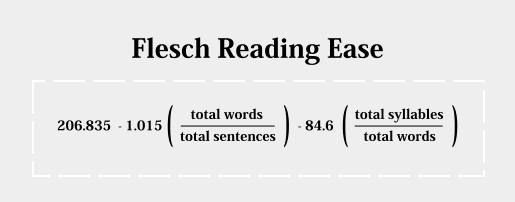

Flesch readability scores are probably the most commonly cited and used of all readability scoring formula. But, what actually are Flesch (1948) and Flesch-Kincaid (1975) readability scores? And what do the scores really mean?

What is a Flesch Reading Ease score?

a score of 70-80 is equivalent to school grade level 7

Flesch Reading Ease (1948) is a readability test. The score on the test will tell you roughly what level of education someone will need to be able to read a piece of text easily.

The Reading Ease formula generates a score between 1 and 100 (although it is possible to generate scores below and above this banding). A conversion table is then used to interpret this score. For example, a score of 70-80 is equivalent to school grade level 7 and should be fairly easy for the average adult to read.

The Flesch Reading Ease test originated from research in the education sector from a need for teachers to choose texts appropriate to the reading level of their student. Yet, its use has always been far more wide-ranging. In the late forties, the creator of the measure, Rudolph Flesch, worked as a consultant with the Associated Press to try and help them improve the readability of newspapers. Now, the Flesch Reading Ease is used by digital marketers, research communicators and policy writers among to help them assess the ease by which a piece of text will be understood and engaged with.

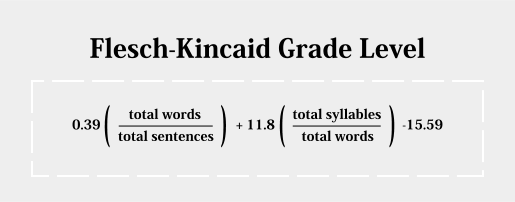

And what about the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (1975)?

In the mid-seventies, the US Navy were looking for a way of measuring the difficulty of technical manuals used by Navy personnel in training. A challenge in using the Flesch Reading Ease measure is that test results are not immediately meaningful. To make sense of the score requires the aid of a conversion table. So, the Flesch Reading Ease test was revisited and, along with other readability tests, the formula was amended to be more suitable for use in the navy. The new calculation was the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (1975).

For the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level test (1975), grade level classifications are based on the attainment of participants in the norming group on which the test was trialled. The grade represents norming group participants’ typical score. So, if a piece of text has a grade level readability score of 6, this is equivalent in difficulty to the average reading level of the norming group who were at grade 6 when they took the test.

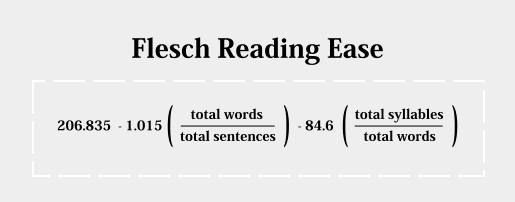

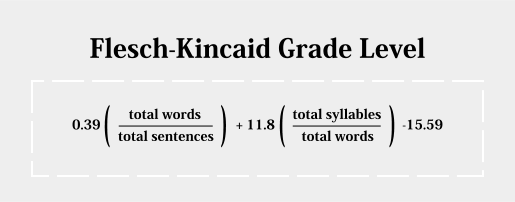

How do the tests work?

If maths is not your thing, look away now.

The mathematical formula underlying the two tests look like this:

For many of us, the sight of a mathematical formula is rather scary. But, the building bricks that make up the formulas are actually very simple.

The formulas are based on two factors:

- sentence length as judged by the average number of words in a sentence

- word length as judged by the average number of syllables in a word.

The rationale here is straightforward. Sentences that contain a lot of words are more difficult to follow than shorter sentences. Just read James Joyce’s Ulysses if you don’t believe me. Similarly, words that contain a lot of syllables are harder to read than words that use fewer syllables. For example, the sentence ‘It was a lackadaisical attempt’ is more difficult to read than ‘It was a lazy attempt.’

Making sense of the results

the weightings differ between formulas resulting in different readability scores for each test

Both the Flesch Reading Ease and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level tests are calculated on the same units: sentence length as judged by the average number of words in a sentence, and word length as judged by the average number of syllables in a word. But, the weightings differ between formulas resulting in different readability scores for each test.

Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease: For Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease, the higher the reading score, the easier a piece of text is to read. Note that this differs from the majority of readability scores where a lower score is easier. To make sense of a Reading Ease score you can use a conversion table to translate their score into a grade level score. For example, a reading score of 60-70 is equivalent to a grade level of 8-9 so a text with this score should be understood by 13-15 year olds.

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level: As stated in the label, the score that is generated by the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level is equivalent to the US grade level of education that the reader would require to be able to understand that piece of text. So, a piece of text with a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score of 8 should be readable by those who have reached the 8th grade of schooling (aged 13-14).

So, which test should I use?

Flesch Reading Ease is the classic of the readability tests

Flesch Reading Ease is the classic of the readability tests. Published in 1948 it was the first of a glut of mid-20th-century readability tests with the Gunning-Fox and Spache both appearing a few years later in 1952. The original and longest established readability test, the Flesch Reading Ease it is used widely by government departments and researchers. Given its durability, Reading Ease is seen by some as a safer bet in terms of generating reliable and valid readability scores.

A possible limitation of the Flesch Reading Ease measure is that a conversion table is required to understand the results of the test. Hence, the reason that the simplified version of the Flesch test formula, the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level measure, was created. The benefit of the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level formula is that the results are easy to interpret with the score matched to the grade level required to read the given piece of text.

When is Flesch-Kincaid most useful?

Flesch-Kincaid readability tests are useful any time you want to measure how easily people can understand a piece of text. Text intended for readership by the general public should aim for a grade level of around 8. So, that’s a Grade Level readability score of around 8, or a Reading Ease score of around 60.

What you might use readability testing for depends on your sector.

You may be:

- a teacher trying to choose textbooks for your class

- a marketer advertising a product

- an author editing your novel

- a researcher trying to communicate your findings to a non-specialist audience

Whatever you are writing, readability scores can give you valuable insights into how easy your text is to understand by your intended reader, in turn, influencing the extent to which people engage with and take on the message you want to communicate.

26 January 2017 | readability |

The challenge

All researchers, at some point, will need to communicate their work to a non-expert audience. You may wish to raise public awareness of a pressing issue. Perhaps you want to change public attitude or behavior. Or maybe you just to get your research on the radar. So, how can you communicate your research in a way your audience will understand?

What is the relevance of readability scores to researchers?

Readability scores provide a gauge of how difficult a piece of text is to understand. Readability-score generates scores on a range of readability formula including grade level. Text aimed at the general public should aim for a readability grade level of around 8. If text is not easy to understand then the reader is less likely to engage. Without engagement, research communication won't result in any changes in knowledge, attitude or behavior.

As well as telling you what the readability of your text is, Readability-score generates a set of text metrics. These include key word density, text statistics, and longest words and sentences. This will allow you to spot where you have overused words or perhaps not used a key word enough. Also, by highlighting long sentences you can easily see where changes need to be made.

What's the evidence?

Well, there's plenty. Many studies have measured the readability of text used to communicate research findings. They typically report a far higher grade level readability score than recommended for the general public. For instance, an evaluation was conducted on the readability of drinking water quality reports for consumers. These reports include important information on detected contaminants as well as educational material. The evaluation found that the reports were written at the 11-14th grade level. This is well above the recommended level of around 8. There is also evidence of poor readability of research participant consent forms. One study reported that average readability was at grade level 13. Again, well above the 7 or 8 typically recommended. So, even in the development of research materials, readability can play an important role.

What value can readability scores bring to the picture?

While readability is certainly not the only factor to consider in effective research communication it is an important factor. Misunderstanding of research and research implications can be anything from annoying to life threatening. Readability-score can help researchers fulfil their responsibility to communicate their research clearly reducing the chances for misinterpretation.

30 November 2016 | readability |

The challenge

As a teacher or other education professional, how do you choose the right reading materials for your learners?

On the one hand, you want those you educate to feel challenged, not bored.

On the other hand, if learners are presented with texts well beyond their current reading level they are likely to struggle and make mistakes. Too many mistakes and too much struggle and they are likely to end up demotivated and disengaged.

What is the relevance of readability scores to teachers?

Readability scores can contribute to informed choices about appropriate texts. Readability-score provides grade level readability scores for a range of formula allowing you to see whether a prospective text is appropriate for your student group. You can then compare readability scores for different texts and make comparisons on their respective levels of difficulty. In this way, readability scores can be used to help you match your class reading materials to the reading level of your learners.

What’s the evidence?

The field of readability measurement came about from education nearly a century ago (for a little bit of history on how readability scoring came about see this article). In 1975, UK education policy highlighted the importance for teachers to assess the level of difficulty of books by applying measures of readability. Since then, readability scoring has been widely use to help inform selection of school reading materials. For example, a survey by the National Council of Teachers in English delivered to English teachers in a Western state in the US found that 84% of respondents identified readability level as a factor that influenced decisions about what texts were selected for English teaching.

An arena where readability scoring may be particularly useful when choosing texts for learners with disabilities. Here, extra careful judgement is required to ensure the chosen texts do not compound the challenges that the learner already faces. In particular, if the learner has been in a position before where they have been shown up in front of others for struggling with a text that was beyond their reading level. Experts on special education, Boyle and Scanlon recommend that teachers choose texts that are at the reading level for their learners and use readability formulas as a guide to selecting these.

What value can readability scores bring to the picture?

Readability scores are not meant to be prescriptive. The careful judgement of a skilled and experienced teacher is always vital for choosing appropriate texts. What readability scoring brings is another source of evidence to help inform reading material selection. Readability scores can facilitate teachers to choose texts that complement the learners reading comprehension, in turn, facilitating effective learning.

14 November 2016 | readability |

Readability: what it is and why it matters

The written word is used to communicate a whole host of ideas and information. But, what if without even being aware of it, the way you were presenting your ideas – the language you use, the length of your sentences, your use of grammar – was actually getting in the way of people engaging with your message? Readability scores are one way in which you can measure whether written information is likely to be understood by the intended reader.

What is a readability score?

A readability score is a computer-calculated index which can tell you roughly what level of education someone will need to be able to read a piece of text easily. The score itself identifies a grade level corresponding to the number of years of education a person has had.

readability of a given text can influence the extent to which people engage

A score of around 6 is the approximate reading level on completion of elementary school in the USA or primary school in the UK, going up to a score of around 10-12 on completion of high school or secondary school.

If text is too difficult or awkward to read then messages may not be engaged with or understood. However, if reading is too easy your audience might feel patronised or just plain bored. Either way the readability of a given text can influence the extent to which people engage with and take on the message of that text.

How did readability scoring come about?

The idea of readability came about in the 1920s. As the numbers of children going to secondary school was increasing, figuring out exactly what these children should be taught became a hot topic. Advice arrived in the form of Thorndike’s (1921) The Teachers’ Word Book. The book listed 10,000 words, each assigned a value based on his calculation of the breadth and frequency of use. The idea was the book could inform teachers as to which words they should be emphasising in their teaching so that those words most commonly used could be instilled in the vocabulary of their students.

the most widely used readability algorithms are Flesch-Kincaid and Gunning‑Fog

Thorndike’s book and its later variations were the catalyst for research into readability, that is, what makes text readable and how this differs by educational level. By the late 40s, measures of readability had emerged generating scores based on syllable counting and sentence length. These scores were often mapped to a grade level.

For example, Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease scores are (usually) between 0 and 100, with a score of 70 to 80, equivalent to 7th grade (age 12), being fairly easy to read. Flesch-Kincaid and Gunning-Fog Grade Levels provide scores directly in grades, where a score of 7-8 is ideal.

Why does readability matter?

Readability is a widely applied principle found to be valuable across a vast spectrum of professions and sectors. Here are just a few examples of why readability matters and to who.

How do teachers decide what texts are appropriate for their students?

With education is at the foundation of society the responsibility on teachers to educate effectively could not be greater. One of the many factors that bear on the success of teaching is whether instruction is pitched at an appropriate level for the learners. Too easy and they’ll be bored. Too difficult and you risk them disengaging all together. Readability scores have long been used by education professionals to help them make decisions about which books are appropriate for their students.

84% of respondents identified readability level as a factor that influenced decisions about which texts were selected

Back in 1975, the UK education policy A language for life set out that “a particularly important teaching skill is that of assessing the level of difficulty of books by applying measures of readability. The teacher who can do this is in a better position to match children to reading materials that answer their needs.” Forty years later, the use of readability scores in the choosing of set texts remains influential.

A survey was conducted by the National Council of Teachers of English in a Western state in the US. 84% of respondents identified readability level as a factor that influenced decisions about which texts were selected for English teaching. While some researchers have highlighted the limitations in the use of readability scores to choose age appropriate texts, readability provides a useful measure by which to contribute, alongside other factors, to appropriate text selection.

How can digital marketers increase the likelihood of people engaging with their brand?

“content that people love and content that people can read is almost the same thing”

As Neil Patel of Content Marketing Institute writes, “content that people love and content that people can read is almost the same thing”. While this may not be quite true – you could convey some fairly rubbish ideas in some easily readable sentences – readability scores can play a role in getting people to your site and ensuring they can easily read your content when they get there.

So, for digital marketers then, readability is a pretty important factor for success. Evidence around the readability of web content, unsurprisingly, shows massive variation between sites. For example, a study of wine websites looking at copy from 20 most popular wine brands in the US found that readability varied wildly. The researchers highlighted that wine drinking is now of interest to younger consumer groups as well as the wealthy – yep, everyone loves wine.

With this wider audience in mind, they concluded that less sophisticated consumers would not engage in messages about wine that they didn’t understand. At the same time, more sophisticated consumers would appreciate information being conveyed clearly. For both markets, paying attention to readability was seen as vital in conveying messages to consumers. After all, if people struggle to even read your content then there isn’t much hope in them actually engaging with your ideas and vision.

How can the legal profession simplify essential documents?

"Have you read the terms and conditions?" "Yes," we say, even though 99% of the time this is probably a complete lie. That said, if those terms and conditions were a matter of life and death then hopefully we’d at least take a glance. The difficulty here is that important legal documents, such as wills, are not necessarily written in a way that people can understand.

legal documents, such as wills, are not necessarily written in a way that people can understand.

A recent study investigated how people comprehend legal language in wills. It revealed that people have significant difficulty understanding the concepts described in standard, traditional wills. It also showed that in comparison to will-related documentation in its traditional format, revising the text to increase readability was seen to improve participants’ abilities to apply will-related concepts and to explain their reasoning. Providing explanation for archaic and legal terms provided a further improvement.

Given that most older adults in the US and UK have a will, the notion that the contents of these important documents, and therefore the implications of having signed one, may not have been fully understood is pretty worrying stuff.

How can governments express their plans and policies in as transparent way as possible?

what are the criteria by which we can judge whether something is written clearly and concisely?

It is the responsibility of any government to communicate their ideas and plans clearly and concisely so as to ensure transparency of their intentions to those people whose lives will be affected. However, as anyone who has ever tried to read a government policy will realise, this is not necessarily something that they are very good at. In recognition of this, there are campaigns in the UK and the US to try and give governments a hand and to promote the use of plain English in government communication. But what are the criteria by which we can judge whether something is written clearly and concisely?

You guessed it, readability scores.

For example, in the US, following the introduction of the Plain Writing Act of 2010, the efforts of government bodies to present their policies clearly is audited annually by the Center for plain English (PLAIN). A report card created for each government department and along with reader reviews, the readability score for documentation is generated feeding into grading. Readability scores then are one criterion by which governments can be held accountable in the generation of transparent policies.

How can the healthcare sector ensure patients are getting the right messages around their care and treatment?

What is lupus? How long does flu last? Is bronchitis contagious? These are a few of the popular Google health searches of 2015. Whatever the condition, type it into your browser and there is a whole treasure trove of information available.

guidance suggests writing for a level of grade 7 or 8

Aside from the enormous issues around the accuracy of medical information online, there are also big question marks around the clarity of how potentially lifesaving information is communicated. Readability scores have been used by researchers to assess the readability of health related communications available on the internet and the results are not very encouraging. For example, a study looking at gastric cancer related information on the web, 51 websites were evaluated found average readability to be at a grade level of 10.4. Given that US National Library of Medicine guidance on writing health material for the public suggests writing for a level of grade 7 or 8, this health related information seemed rather poorly pitched.

The same pattern was found in a study assessing the readability of health information presented by organisations representing the top 5 medical-related cause of death in the US including diabetes and stroke. Again, readability scores were well about the recommended grade 7 or 8. Given the potential seriousness of misunderstanding health related information, the need for health related communications to be pitched appropriately for the reading levels of the general public should not be underestimated.

So what is the potential?

Readability scores don’t just point out problems, they provide a tool by which to address them. Readability measures help highlight issues in readability of health related information. They help communicators ensure patients can understand the important health messages being conveyed in information leaflets. They help to point out weaknesses in government communications, by giving policy writers advice on the readability level they should aim for. And when writing for the general public, readability scoring provides a gauge by which writers can improve the quality of their writing.

23 July 2016 | readability |

The English language is known for some interesting twists and turns, a tradition that continues with the naming of US towns. The reasoning behind some of the more unusual names is often as obscure as English word origins, but it does make travel through the US interesting.

1. If you're traveling below the Mason Dixon line, take note of town names like Jot 'Em Down or Climax, Georgia. There's no affiliation between Climax and Intercourse in Sumter County, a historic area producing wheat, peanuts, and cotton. It sports a decent population of around thirty thousand, in direct contrast with...

2. Nothing, Arizona. The American West is known for its big, empty spaces, but it's the little things that count - or don't, depending on how you reason. Nothing, Arizona is a literal wide spot in the road twenty miles south of the "Rattlesnake Capital of Arizona." It's been abandoned because its tiny industries have come to, you guessed it, nothing. No surprise there. However, Surprise, Arizona sports a population of over 100,000 and is in close proximity to Luke Air Force Base. Clearly, there's nothing small or inconspicuous about Surprise, yet travelers find its name a little - surprising.

3. If you're traveling in the Midwest, check out Devil's Elbow, Missouri, named after a tricky bend in the Big Piney River. It rests on historic Route 66, but visitors may be disappointed if they're interested in visiting the site of the not-so-famous Devil's Elbow Cafe. The area is currently being rebuilt after flooding in 2017.

4. New England is a beautiful locale that is clearly hiding some real gems, like Satan's Kingdom, an unincorporated area in Northfield, Massachusetts. How the area came to be called Satan's Kingdom isn't clear, but at least one YouTuber believes the name developed out of nicknaming to warn people of poisonous snakes and other dangers in the wooded area. Got it - be wary of Satan's Kingdom.

Road tripping around the US offers valuable experiences. Don't forget opportunities for selfies with some odd and entertaining road signs!

17 July 2015 | english quirks |